Over the last year, I have been investigating the warping of space in images. It began as an exercise in trying to understand the feeling of wide lenses vs. long lenses, and as a special curiosity toward the flatness of certain medium format photographs. I am still not entirely able to pin down what “it” is. It usually has something to do with the deep focus of the image, the composition in relationship to the eyes of the subject, and the apparent absence of barrel distortion.

In another way, what gives an image a different sense of presence? What are our subconscious clues that we are looking at a photograph, and how is that separate from how we construct images in our minds?

Cropped images can eliminate barrel distortion, or sample a flatter range. I believe that the landscapes we see in our mind tend to be collages. When you look at a drawing or painting, space is affected by insertion of things that were not; subjects and objects paid attention to a moment at a time.

Scannography follows this same wandering mind. Distortion of objects is not a matter of space, but of time. There is a flatness discovered in the simplification of drawing. A broadness and evenness to lighting impossible to source. A dreamy shallow depth of field to mimic the vagueness of memory. And a bizarre extended technique of creating new nameless anatomical features by gestures of the body through time; Bellmeresque distortions of the body.

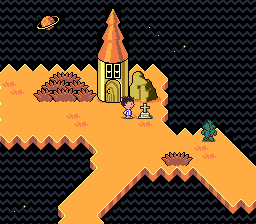

I’ve been looking back into Cezanne, the cubists, and the Weimar Republic painters for new insights. New to me, anyways. This added to my permanent fascinations with 8-bit video games, Meatyard, Fellini, and Parajanov.

This constant awareness of space has begun to affect my dreams. Last night I was lying about with random friends playing these large handheld arcade games. About the size and shape of the new Lite-Brites. Some strange version of Ducktails, I believe. In the bottom third of the screen, the characters raced in an alley in front of a picket fence. Behind, and so above, were suburban houses uphill with all manner of strange repeating structures and rolling obstacles tumbling down. All moved sidescreen, which in the heat of the action would become live. Short spiraling picket fences, up the side of the hill, with photographic brothers inside throwing stones as we ran in duck suits through the alley. In my lucid awareness, I rewound and reviewed the memory, again and again, until it became too unstable to be conclusive.

Meditation in life is merely practice for the dream world.